Superhuman River: Re-Enchantment at Gaumukh

In the summer of 2009, I trekked to the Gangotri glacier, the rapidly melting source of the Bhagirathi—one of the two glacial streams that join to form the Ganga. I longed to touch the glacier terminus, where ice and debris hang in the shape of Gaumukh, the ‘Cow’s Mouth’, before it disappeared. The East India Company sent an expedition to find the source of the Ganga as early as 1808, but the expedition failed to reach Gaumukh and declared that the Ganga ‘emerges from a spot beyond human reach’. (Opinions change: in the previous century, British surveyors had emphatically declared that the Ganga was a man-made river originating from ancient canals.)

The region remained unmapped until 1935 and the road to the town of Gangotri was built as recently as 1984. Even today, cell-phone reception cuts out past the town. To reach the 13,500-feet-high glacier, I would have to walk more than 17 kilometres without passing a rest house. For six hours I rode towards the trailhead in the back seat of a shared jeep with a plastic vial of Ganga water dangling from the rearview mirror and a religious chant playing on repeat. My companions were men and women who lived in tiny hamlets along the way to Gangotri.

The vial lurched this way and that as we lumbered along the muddy mountainside, waterfalls splattering the roof and windows of the car, a landslide halting us for two hours. No one paid much heed; as long as the water was there, they were safe.

Rattled by the drive, a part of me wanted to share this folk belief as earnestly as I had once chanted ‘Ganga, Ganga’ while pouring water from the bucket baths over my head when I was a child. Another part of me stood apart. Did venerating Gangajal mean accepting darker superstitions about gender and caste that my mother and I had tried, often painfully, to unravel ourselves from? And why bother with these questions when many people said that the Ganga and its glacial source were receding almost beyond recognition?

Two hours from town, the jeep picked up Mangal Singh, the man who had agreed to guide me through the Gangotri National Park. Mangalji was a small man with a narrow face, broad shoulders, and a Charlie Chaplin moustache. His chocolate eyes glowed as he told me he did his ‘B. A. And M. A. At the same time’—when he was fifteen; he’d successfully enrolled in both the introductory and the advanced classes at the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering. He also informed me that he had discovered more than eighty trails in the state of Uttarakhand, trained the Indian army in scaling glaciers during the Kargil War in Kashmir, and walked the entire length of the Ganga with a German scientific expedition researching the river’s ecology.

At the end of the road lies the town of Gangotri, a clot of shops and priests where buses bearing pilgrims arrive every afternoon.

They go to the temple of the Ganga and walk down to the riverbank to marvel at the statue of King Bhagirath, who is said to have brought the river down from heaven through his centuries-long meditation. For most pilgrims, this is far enough. Long before sundown, they climb back into their tour buses. A handful of people, however, push on to the snout of the Gangotri glacier, one of the holiest spots in Hinduism. In recent years, tourism has massively increased; in the past, when trekking to the glacier was near impossible, people treated their village pond as equally sacred, and occasionally worshipped returning pilgrims as deities.

The first segment of the eleven-mile trek to the glacier is an upward-sloping exposure chamber, vast and isolated. Distant snowcapped Himalayan peaks drift into view now and then, but the barren foothills—craggy, sulphurous heaps of rocks and dust—dominate the landscape. Against this relief of massive lifeless rocks, the Ganga, known here as the Bhagirathi, is a delight: a clear, narrow stream, bounding with energy and potential. Thirsty creatures dot the mountainside—black snakes and ibexes, bulbuls and monals, white birches and junipers.

Mangalji greeted, with a namaste, not only the river, but each creek and stream we crossed. Self-consciously, with a when-in-Rome attitude, I too folded my palms before crossing over.

After hiking more than 8 kilometres in five hours, we reached Chirbasa, a nursery of silver pine, spruce, blue fir, and cedar trees; the Nepali guards invited us to stay, but Mangalji wanted to keep going.

We were aiming for Bhojbasa, a makeshift camp 6 more kilometres away. We walked through a pine forest, dark and dense after the bald terrain we’d been traversing, and Mangalji told me that there had been more forested paths along the trail until pilgrims cut down the trees for firewood. Below us, a pika scampered away, already on guard.

The altitude made me light-headed and slow and I developed a newfound respect for pilgrims who try to outdo each other in athleticism while travelling to the headwaters of the river, as if feats of endurance are a strategy passed down from Bhagirath himself. I had to rest frequently under rocky overhangs, measuring my distance from one patch of starry wild-flowers to the next, from a stand of pines to a stand of grizzled birches. I breathed heavily, my whole mouth open, and forged ahead only because it would be humilating to collapse. The words of James Baillie Fraser, a Scottish traveller and watercolourist, who, in 1815, trekked to the town of Gangotri with his brother, an officer in the East India Company, spurred me on:

‘So painful indeed is this track, that it might be conceived as meant to serve as a penance to the unfortunate pilgrims with bare feet, thus to prepare them and render them more worthy for the special and conclusive act of piety they have in view as the object of their journey to these extreme wilds.’

The Gangotri glacier has receded more than one-and-a-half kilometres since Fraser tried—unsuccessfully—to reach it.

I walked on, wondering how long the object of my pilgrimage would endure. I had never climbed so high before. Mangalji found a rough aricha leaf and insisted that I chew it to combat nausea. The aricha tasted like nothing but a leaf, with no distinguishing characteristics or immediate effects, but I kept it in a corner of my mouth, drawing it out, eager to absorb a bit of the unworldly landscape. After eight hours, it finally became clear we couldn’t reach Bhojbasa before nightfall, and so we settled in a shack owned by trail workers, where we slept without awkwardness on the same crude planks. That night I dreamed of a bird I’d seen near a house I once shared in South India—the Asian paradise flycatcher, a small white bird with a long, white, ribboning tail. I’d first seen the bird in a forest in Kerala, then once more on a garbage heap next to my window in Tamil Nadu.

I had learned in that instant that wilderness could exist anywhere, not just in the wild. The next morning, I awoke filled with tranquillity and wonder. When I woke up I noticed graffiti on the wall of the shack—crudely formed Hindi letters that read ‘Water is Life’.

As we plodded along the icy, burbling river that morning, our path crossed with a swami known as Maharaj. He wore sunglasses and tennis shoes, and was accompanied by four portly women from the neighbouring state of Haryana. The party had turned back after seeing a crack in the ice. ‘I would have had to roll these four along like drums,’ Maharaj said. I asked him whether he thought the glacier would melt within his lifetime.

‘It’ll take longer,’ he said confidently. ‘At least fifty years. But even after she’s gone, those of us who truly love her will still be able to see her.’ I asked what he meant.

‘Most of you are living in the Kaliyuga,’ he said. ‘Only a few of us have escaped into Ram Rajya, the age in which we can think completely for ourselves, where our minds are free. We are free of the Kaliyuga.’ But Maharaj had not transcended the physical world entirely: ‘We used to take the snow, melt it with some jaggery, and eat it as a snack,’ he said. ‘Today, we can’t do that anymore. The snow is greasy and black from vehicle exhaust.’

A few minutes later we reached a field of boulders, which travellers had piled up like cairns. Ahead, the snout of the glacier gleamed, the river thundering out of its icy encasement. In every photograph I had seen, this spot looked barren, discoloured, and stony. But as I sat there, cross-legged, I marvelled at the spots of colour pulsing all around me: tiny pink, yellow and purple wild flowers, complex leaf patterns, and minute crickets that looked as drab as dead leaves until they unfolded their ruby wings. I poured my Gangajal on a small shrine made of rocks.

I felt good, wholehearted, if not enlightened. The pilgrimage hadn’t been so tough—just a series of bus rides and walks and one long haul at the end. I tried to imagine the whole sweep of the river, across time and space—the East India Company sailing down the Ganga into Kolkata, which they made the capital of their empire, with floating logs, opium, and slaves down the river that had received the ashes of my ancestors and millions of others; the industrial effluent from tanneries mingling with corpses, sewage, faecal bacteria, and increasingly salty tides carried in by the rising sea. The Ganga was still alive, in spite of everything.

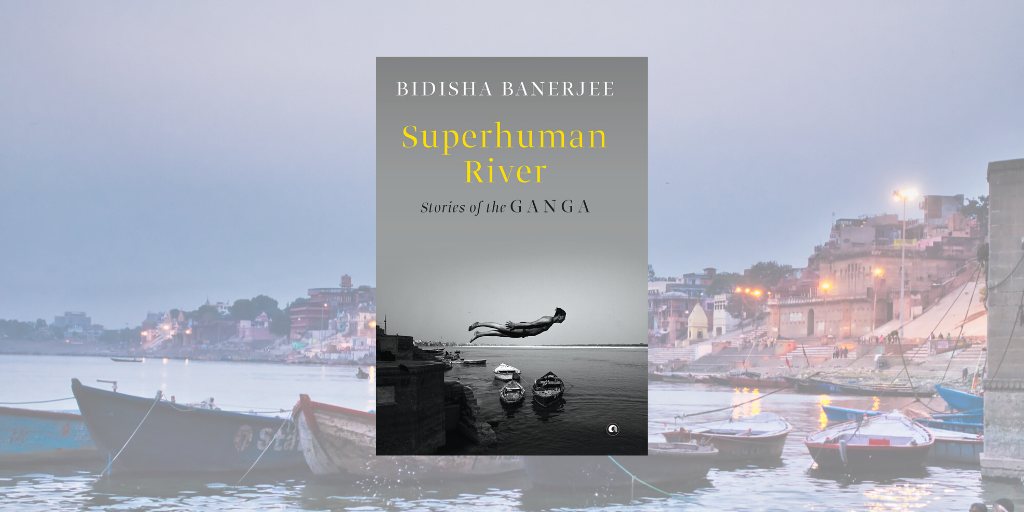

Read more with Bidisha Banerjee’s Superhuman River