Gazing Eastwards by Romila Thapar

THE START OF THE RETURN JOURNEY VIA YUMEN

We are journeying back. I am sitting in a hotel room in Yumen, drinking cup after cup of jasmine tea. I feel so thirsty. After the slightly brackish water at Dunhuang, it’s so pleasant to have ‘sweet water’ again. I indulged in another orgy of bathing today—a steaming hot bath, after many days of lukewarm catlicks. I never feel really clean until I have washed behind my ears and cleaned my toenails. We had some European food for dinner—tastes awful after Chinese cooking, and I felt so strange handling a fork and knife after so many weeks with a bowl and chopsticks. We saw a radio in the room and I was ecstatic at the thought of some news at last—perhaps the BBC. We battled with it for an hour, and all we got were whirring sounds, or else Chinese and Vietnamese programmes—a fleeting snatch of an Indian film song, which rapidly vanished, and to my great sorrow never returned. So we decided to abandon the radio and write letters instead. But somehow, I couldn’t. I feel tired now and maybe I shall sleep. Two Chinese boys are playing ping-pong in the hall outside, and the steady knick-knock of the ball keeps me awake.

Yumen is an oilfield, discovered about twenty years ago, and set up in the last two years. We decided to come here for a day on our way to Jiu Quan because Dominique wanted to make a ‘story’ about the Old Silk Road having now become the ‘New Oil Road’. The oil from both Yumen and another source in Xinjiang goes to the refinery at Lanzhou. I tried telling Dominique that historically her comparison is invalid because the Silk Road functioned altogether differently—but for a journalist what matters is that it is a ‘catchy story’!

I don’t like this hotel. It smells of colonialism and bad taste. Architecturally, it is badly designed. For the rest, it has central heating and all mod cons. It is inartistically furnished because obviously some poor chap with a wholly Chinese background was trying desperately to bring in things that would make the foreign experts—Russian and East European—and foreign friends feel at home. The hotel is built for these two categories of people. We belong to the second, of course. The large cumbersome-looking armchairs, upholstered in a big-patterned textile with lace antimacassars and the flowered plastic tablecloths on the dinner table—somehow give me whiffs of the Leningradskaya again.

When we arrived we bumped into a very sour-faced Russian woman, quite terrifying—and another two who stared down at us from an upstairs window. I was reminded immediately of colonial wives in the time of the British Raj. That is why, I suppose, I smelt something of the colonial attitude. This may be a wholly unfair judgement. Perhaps they have social contacts with the Chinese—perhaps the relationship is different. Most of the experts are here for three or sometimes more years. Why can’t they live in houses alongside the Chinese—why must they huddle together in a hotel? The country is strange, the culture is different—that is understandable. It is difficult for a Mrs Podsvinov coming from a small-town Russian background to hobnob with the Chinese from the start. But if they are here as friends, and they are genuinely respected by the Chinese, as one is told that they are, there should be no special attempts to house them differently. Possibly this is just Chinese courtesy and politeness again… Ah, the ping-pong has stopped. Now I can sleep.

I feel quite shaken up with the last 30 kilometres of our journey: jolting along a rough track, through streams and ditches and up mounds. The poor Land Rover really rattled like a tin can. But it was an enticing landscape. Desert around us with variegated sands—green, red, yellow in streaks— and mountains, purple, blue, blue-black, violet, red, pink, yellow, changing colour in the changing light, all dappled with the shadows of the isolated clouds moving across the sun in a clear sky. There are fields in some parts and the rest is covered with a yellow-green scrub, interspersed with curious rock formations set in layered earth. Sometimes, it looks like the moon landscape. I wish I had taken the trouble to read at least the elements of geology with reference to China before coming. To pass through such country and not know how it came about is a real shortcoming. There were moments when it was even more fantasy-ridden than a colour film on a sci-fi dreamland.

The little village on the top of the red sandstone cliff evoked endless stories. Empty desert for miles and then the daemonic sprawl of the oilfields; it looked so powerful and menacing under a storm cloud, in the dark evening light, with its silver tanks shining like monstrous eyes. As we came closer,it became quiet and more like a town—or a town where something is happening. It has the magic of an oil town, with the drills and jets and cranes and tanks and the dark pools of oily surface. If this can be called magic? There were crowds of people playing baseball in every inch of free space. They play baseball everywhere—it seems to have become the national game. I walked down the street later. Men and women in groups together and movement all over—and watermelon peels in large heaps. Many of the faces are familiar from a type one meets in northernmost India and these, I am told, are the Uyghur minorities. The women are quite lovely. We lunched at Yumen Xian, a small halting place, where the road turns off for Yumen from the main road going to Dunhuang. There were groups of people with baggage all over the place, waiting to catch a bus and move on. I noticed the inns and restaurants had signs over the door in Chinese and also in Arabic. The Arabic signs usually read ‘Musulman Serai’. It is surprising that the Muslims still maintain their exclusive eating places, probably serving halal meat and no pork, and pork is important to Chinese cuisine. Their women wear black veils over their heads, but the veil is thrown back, revealing their faces—and just as well as they are impressively good looking!

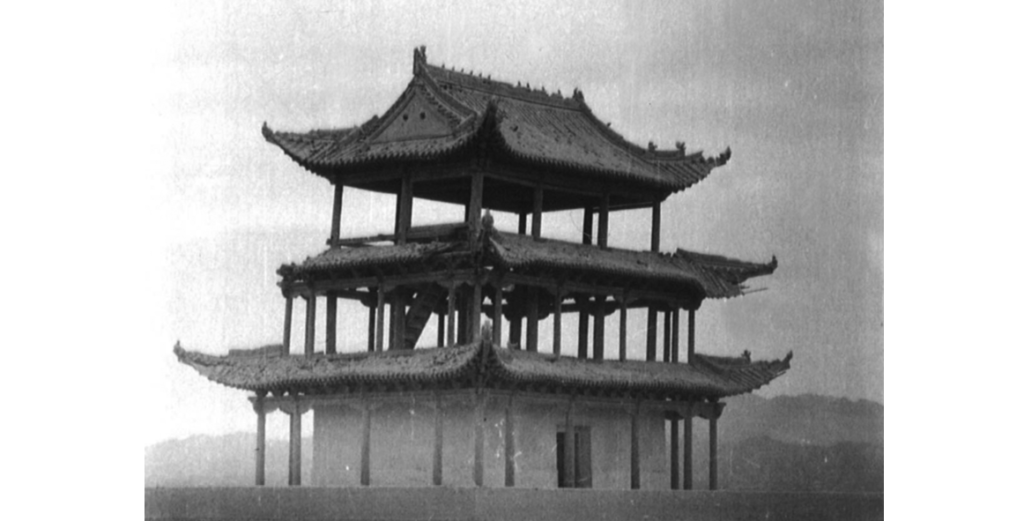

The countryside is studded with what seem to be lookout towers built of mud set in encircling walls—vestiges of the conditions existing ten years ago. It is impossible to believe that as recently as that all this area was banditridden and highly unsafe. That the road on which we travelled did not exist. But more than that, it would have been almost unthinkable for four women to make this journey unless heavily escorted by an armed guard. These are all borderlands and frontiers of earlier times with a scatter of garrison settlements, some of which developed into centres of exchange in the Central Asian trade. The aridity is partly of modern times and resulted from changes in the ecology produced by mining in the region, and the extensive deforestation wherever there were the occasional forests.

***

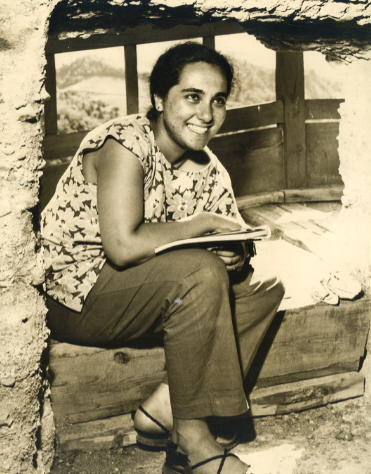

Gazing Eastwards is a lively and arresting account of Romila Thapar’s first visit to China in 1957. She went as a research assistant to the Sri Lankan art historian Anil de Silva, and worked on two major Buddhist sites in Maijishan and Dunhuang. It was a period of deceptive calm in the country, just prior to traumatic events such as the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward that churned and transformed Chinese society. Although China was changing with Mao’s rise to power, much of the old ways remained. This being her first visit to East Asia, the author was greatly intrigued by the country, its culture, and its people during the months she spent there.

Besides her work on the Buddhist sites that brought her to China, the author was able to travel to the historically important cities of Beijing, Xi’an, Nanking, and Shanghai, as also some small cities and villages of the Chinese hinterland. She travelled by plane, train, truck, and automobile. Her curiosity led her to many meetings with a variety of people, great and small, as well as forays into the country’s art, music, culture, and religion. She ate the most unusual and delicious Chinese meals, and endorsed the claim that Chinese food is one of the world’s great cuisines. She delved into Chinese history, learnt how to play the erhu, heard the operas of diverse regions, shook hands with Chairman Mao, admired the grace and beauty of Chinese women, and tried to experience as much of Chinese society as she could. Her observations of her time in China provide the reader with a profound, funny, original, and constantly insightful look at one of the world’s oldest and most complex countries.

Get the book here.

***